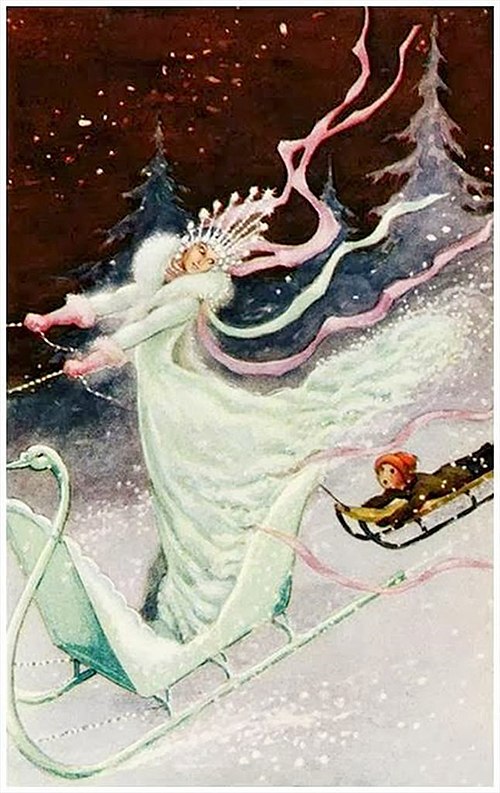

(From an image by HA Maddick)

No evil dooms us hopelessly except the evil we love, and desire to continue in, and make no effort to escape from.

George Eliot, Daniel Deronda

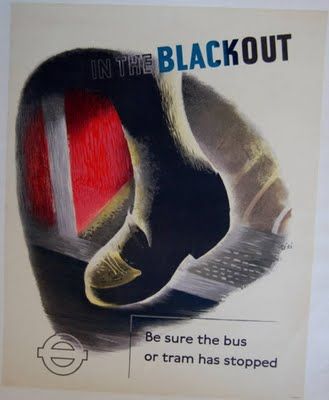

Five minutes is all it takes. Five minutes of violence in the wartime blackout. Five minutes that cast a very long shadow.

After war ends, little Kenny lives with his granny who can’t find words to explain where he has come from. He knows not to ask.

His friend Gemma only knows her daddy as a framed picture on her mother’s dresser.

As the children grow up, they become aware of yawning gaps in their histories. They each meet a person offering shelter and warmth. But at what cost? What to do when a shelter becomes a cage? Who can dare to bite the hand that feeds?

Available in paperback and as an ebook from 11 August.

ISBN 978-1-80042-079-3 (paperback)

RRP £8.99

Available to order from all good bookshops, on-line retailers, or www.silverwoodbooks.co.uk from 11 August 2021

The story of the story

Of all the stories I read over my years of working with children, the Snow Queen has stayed with me as one of the most powerful and many layered. It crept quietly into my adaptation of my mother’s wartime fiction, ‘Bombweed’ and it gently nudged me towards the writing of ‘Kissed to Death’.

What started as a musing over a cup of coffee in my kitchen about a short story idea… two small children, as in The Snow Queen, playing together in the bombsites of devastated Portsmouth until adolescence sends their friendship spinning apart…took me into the dark realms of grooming, coercive control and those wartime secrets which left their mark over those growing up in the shadow of war.

Reviews

Gemma and Kenny are children of the war who, like all too many at that time, live out a childhood where one or even both parents are absent.

Constantly together when small… as they pass through a post-war education system that separates and grades them, their lives move in different directions. What they continue to share, however, is the legacy of lost parents, and, not unrelated to that, they both find themselves caught up in relationships characterised by different kinds of coercive control.

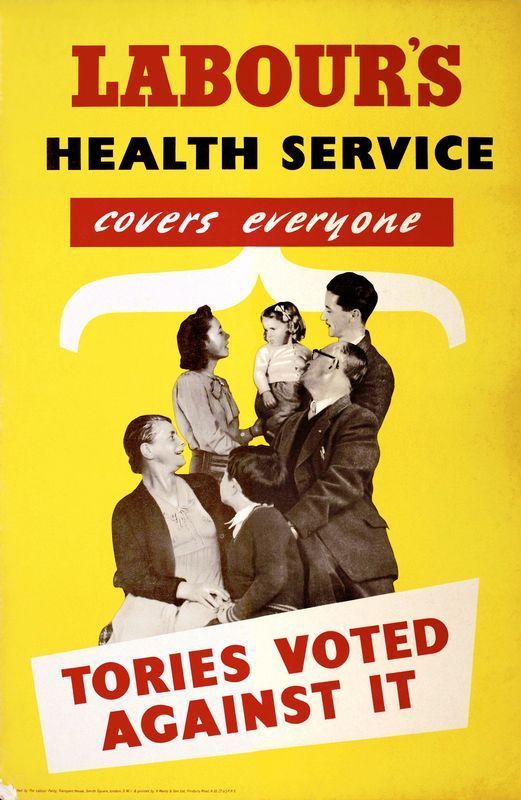

Kissed to Death catches something of the accelerating and widespread social and cultural change that took place in the UK between the end of the war and the rambunctious arrival of the 1960s.

Azule

Secrets, guilt and shame all play a part in this sensitive portrayal of two families as they cope with the fallout from the effects of war…an engaging and revealing read which captivates the reader from the start and holds their interest until the end.

Thelma Howland

…delighted by it. The two young people have a very deep experience of loss in common and are bound together despite other relationships and events which separate them at times…I almost felt as if I ‘knew’ them and felt a warmth for them both.

Heather Geddes

The sadness and sense of how lost these two people were as a result of their personal legacies was palpable. The story reflects their misguided attempts to find emotional connection and a sense of self and identity…That their stories ultimately come full circle in the process of their individual self discovery made the journey with them gratifying.

Rachel Prendergast

Kissed to Death’ is yet another confirmation of Morton’s gift to create and build fluid story. Engaging, intriguing, observant…

Adriana Jurczyk

Morton brilliantly captures the little anxieties and pleasures of childhood: the first day at school, taking part in the local town fancy-dress parade, shy friendships…Woven through the narrative are fairy stories and fables which speak to ambiguous relationships of power, seduction and control that we cannot always fully understand or articulate to ourselves…I found this a gripping read and particularly vivid in its portrayal of childhood friendship.

Jennifer Wallace

Prologue

Even now, when she shuts her eyes, she sees him. It was the smell of him that had come first, even before she heard him emerging from behind that tree in the dark of the blackout. Beer, cigarettes and something else, something sour

and animal-like. A smell which, after it was over, clung to her. Yvonne had been walking across Southsea Common on her way home after the evening shift in the King’s Arms. She’d liked the space after an evening of noise and crowds in the bar. These days the blackout never bothered her. The faint light from her torch was enough to see her feet. It was July so it wasn’t cold, but the wind was suddenly quite strong.

No one was around to hear her cry out. Then she was sure he’d have hurt her more if she’d shouted out again, once he’d got her arms tight from behind and was wrenching her dress up, forcing her legs apart, shoving her face against the tree. The taste, the feel of eating bark. The sharpness of his knees against the back of her thighs.

A feeling of being ripped open, and the horror when he’d gone. She could hear his boots stumbling, running across the grass, leaving behind his smell. If she gets a waft of smells like that in the pub, or on the Underground of an evening, she has to stop herself from retching. Even now.

Somehow, she’d got home, got herself up the narrow stairs, trying to stifle the sobbing so Mum wouldn’t hear. Mum mustn’t know. First to the bathroom, dragging her damp flannel from its hook, scrabbling to turn on the tap to wet it, desperate to get clean, washing and washing, again and again, then to crawl into bed with her flannel between her thighs, horrified at the sight of the blood, and turned to put out the light. Trying not to cry with the pain, she’d called out to Mum to say she’d eaten something bad – didn’t want anything – ‘No, nothing, thank you!’ Would she ever want to eat anything again? Or look at herself in a mirror?

When she missed her periods, Yvonne had wanted to get rid of it, hated to feel the alien presence of something growing, something left inside her by force. It wasn’t long before Mum realised what was up. They’d argued and argued about getting rid of it, giving it away, but her mother was adamant that it wasn’t the baby’s fault. Any baby deserved love. And she could help Yvonne bring the poor little thing up, couldn’t she? Her mum said they’d tell people Yvonne’s secret “fiancé” had gone down with his ship in the Pacific. There were a lot of stories like that in wartime and people could think what they liked. But however many times Mum said “baby”, Yvonne could only think of an “it”.

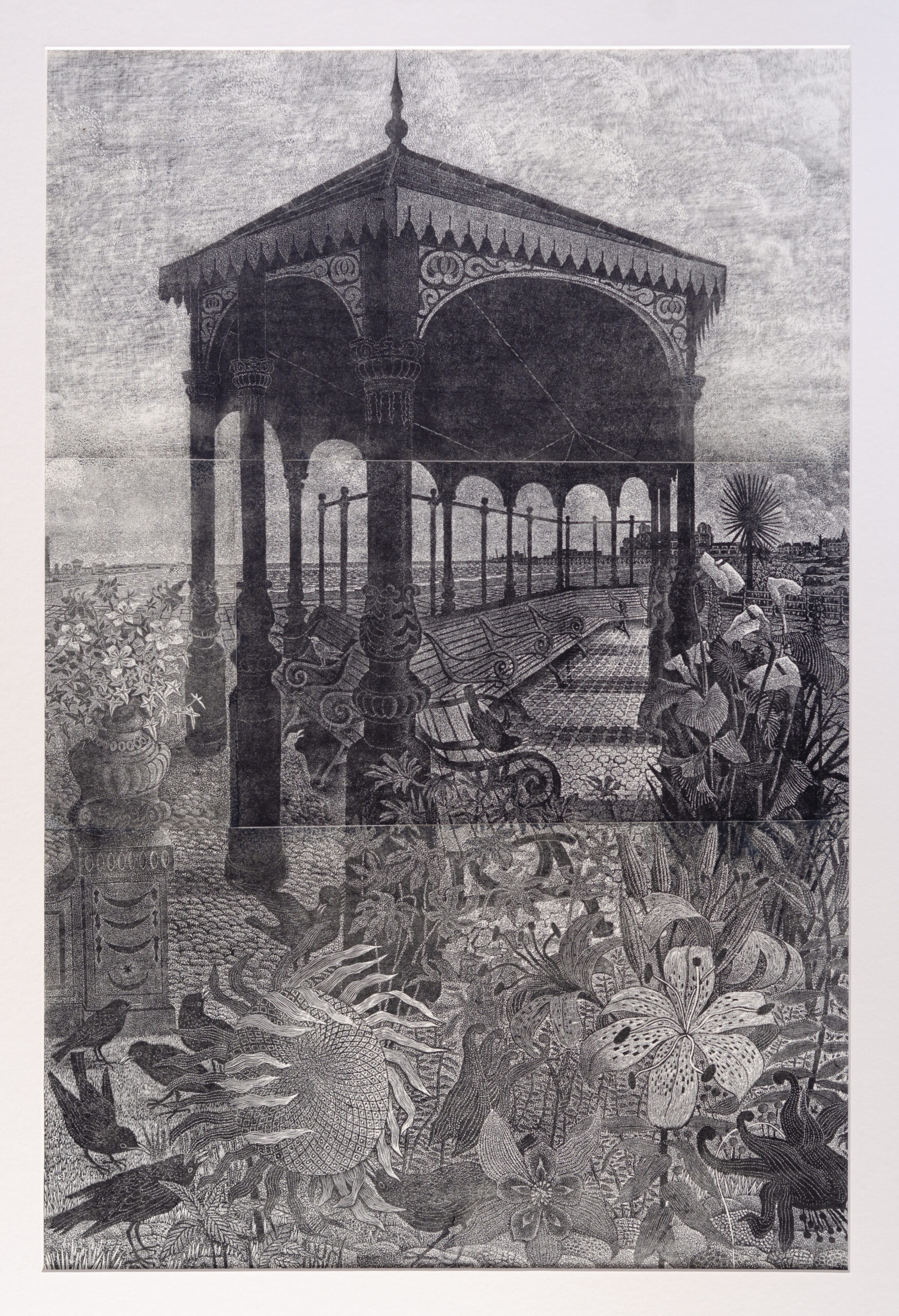

After the boy’s birth – again, a feeling of being ripped open – Yvonne had tried, she really had, but seeing it looking up at her, she knew it’d be seeing a piece of trash, a dirty piece of… like she saw if she ever looked in the mirror. She knew she’d have to go away. Felt bad about taking the money from Mum’s old jam jar on the mantelpiece, but she’d needed it for the train fare to London. Easy to lose yourself up there, people told her, to get some kind of a job in a bar or a club.Andsoitwasall right, in a way, apart from the disgusting smell of beer and sweat from the men that made the bile rise up. And, of course, the dreadful raids, interrupting conversations or dreams. Mind you, she did find herself drifting off sometimes when it wasn’t too busy. Would find herself back on the seafront. Before the war started and all the barbed wire blocked it off. Watching the waves with Mum in the old shelter, smelling the seaweed, hearing the seabirds squealing and quarrelling. Sitting out of the wind and staring at the boats on their way to the Isle of Wight. Her mother was always saying how one day they’d go on one of those big ferries for a treat. Have ice creams on Ryde Pier and even a donkey ride. But it never quite happened. Now, up in London, the Second Front was all people talked about. And of course, the doodlebugs. People often said, carelessly, ‘if it’s got your number’, but you could see the fear that still flickered for a moment over some part of their face.

Back in her tiny London bedsit, Yvonne is carefully scraping out the last of her lipstick with an orange stick, then spitting onto the remaining scrap of mascara, getting herself ready for the evening shift at the pub. When she hears the approaching roar of a doodlebug, she thinks, everyone says you are OK if you can hear it but when the noise cuts out— In the sudden silence Yvonne catches a glimpse of her own terrified face in the mottled mirror, a second before the house fragments around her.

1948

Elizabeth

Elizabeth realises she’s been so caught up in her own thoughts that she’s stopped pegging out the sheets. She reaches for the next damp, heavy whiteness to lift, spread and clip to the line. As the slight breeze lifts a few strands of hair off her face, she looks up, her attention drawn to the small biplane slowly making its way across the blue sky towards the sea. A good drying day, she thinks. Nothing to worry about now, but she’s never lost the habit of listening out for a plane’s engines, feeling a tiny sense of relief when it’s gone on its way. Silly really, now the war’s well over, but she knows she’s not the only one. Those years here in Southsea left their mark on most people. After the Phoney War there was the shock at those first raids and then all the getting used to new things like the siren (Moaning Minnie everyone called it) that could turn your legs to jelly – running for the nearest shelter if you were out in a daylight raid – then the anxious hours waiting for the “raiders passed” signal. Nights huddled in the Anderson shelter, wondering what you’d find when you emerged, which house collapsed, which neighbour caught, either out in the street or under a falling wall or roof. People disappeared in so many ways. Everyone said they got used to it. ‘If it’s got your number on it…’ they’d say, before complaining about the lack of soap or butter.

Elizabeth bends down to separate two red woollen socks embracing in her basket, and stretching back up, pegs them next to the last sheet before putting a hand to her spine, rubbing the stiffness as her thoughts drift. When someone just didn’t come back…from abroad or just from the shops…or going off like Sarah’s daughter, Yvonne, so soon after she’d had baby Kenny. All too hard to get one’s head around. Someone you knew well enough to store a picture of them in your head, someone maybe you’d been impatient with the last time you’d seen them…and then nothing. Sometimes you’d see the telegram boy on his way to a door. Sometimes literally nothing. Like old Mrs Mortimer, the doctor’s wife from the next street. Caught in a raid on her way home from the WVS. Nothing much left to put in the coffin, but no one said that out loud in front of the family. But her poor daughters…